Mag

The Ultimate Guide to Turquoise: History, Value, and Care

Unveiling the Sky Stone

Turquoise, derived from the French pierre turquoise (Turkish stone), is one of the oldest known gemstones, treasured by cultures across the globe for millennia. This vibrant blue-to-green mineral, a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminum, captivates with its unique color palette and historical significance [3]. The name itself hints at its historical trade route: the stone was often brought to Europe via Turkish merchants, even if its origin lay in Persia or Egypt. The stone’s striking appearance, ranging from the deep, pure blue often associated with high-altitude desert environments to the greener shades found near iron deposits, ensures its constant demand in the gemstone market. Furthermore, the subtle variations in matrix patterns allow every genuine turquoise specimen to be unique [1]. Its inherent beauty lies in this contrast—the ethereal blue set against the earthen matrix—making it a favorite among jewelers and collectors alike.

Chemical Composition and Structure

Turquoise belongs to the triclinic crystal system and is chemically defined by the formula: 6 CuAl (PO ) (OH) ⋅ 8 4H O2 CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8⋅4H2O \text{CuAl}_6(\text{PO}_4)_4(\text{OH})_8 \cdot 4\text{H}_2\text{O} 4 4This structure clearly shows the essential elements: Copper (Cu) responsible for the blue coloration, Aluminum (Al), Phosphate ($\text{PO}_4$), Hydroxyl groups (OH), and water of hydration ($\text{H}_2\text{O}$). The presence of water in its structure is critical, as the loss of this hydration can lead to dulling or color changes over time if the stone is subjected to excessive heat or dryness.

A Brief History & Cultural Significance

Turquoise has held profound meaning for civilizations throughout history, often serving as a talisman of protection, wealth, and health. Its presence in archaeological sites spanning continents attests to its universal desirability. Its historical narrative spans continents, connecting ancient metallurgy, spiritual beliefs, and international trade routes. • • • • Ancient World: Found in Egyptian tombs dating back to 3000 B.C., it was used both as jewelry and for ceremonial ornaments. Pharaohs and royalty adorned themselves with turquoise, believing it offered divine protection in the afterlife [3]. The Egyptians mined turquoise extensively in the Sinai Peninsula, referring to it as mefkat, often translated as “stone of joy.” The Persian Connection: Historically, the finest quality turquoise, often characterized by a pure sky-blue hue without webbing, originated from the Nishapur mines in Iran (ancient Persia). Persian turquoise has long set the global standard for quality, often termed “Robin’s Egg Blue” in modern descriptions [1]. This specific color grade is highly coveted due to the region’s unique geology, which lacks significant iron contamination. Native American Cultures: In North America, particularly among Southwestern tribes such as the Navajo, Zuni, and Hopi, turquoise is sacred. It often symbolizes water (life) and the sky (the divine), and is integral to spiritual and decorative arts [2]. For these cultures, turquoise is not merely ornamentation but a living extension of the earth and the heavens, frequently incorporated into ceremonies, healing rituals, and the creation of elaborate silver jewelry. Global Trade: During the Middle Ages, turquoise was highly valued in Europe and the Middle East, where it was believed to protect horses and riders from falling, leading to its inclusion in ornate bridles and equestrian gear.

Geology & Formation

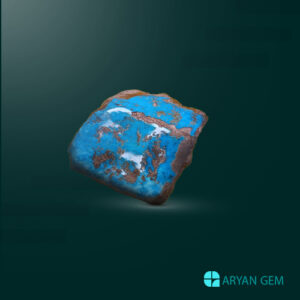

Turquoise is a secondary mineral, meaning it forms near the Earth’s surface when acidic, copper-bearing groundwater interacts with aluminum-rich rocks like feldspar. This geological process requires specific environmental conditions, including the presence of copper, aluminum, phosphorus, and water [1]. It typically forms in arid regions where evaporation concentrates minerals near the surface. Its color is directly influenced by its chemical composition, specifically the metal ions present in the crystal lattice: * Blue Hues: Indicate higher copper content ($ \text{Cu}^{2+}$). The purest blue forms when copper dominates and iron is absent or minimal. * Green Hues: Suggest the presence of iron ($\text{Fe}^{2+}$ or $\text{Fe}^{3+}$) replacing some of the copper in the crystal structure, or the presence of zinc. Green coloration is often associated with older, weathered stones or specific deposits, such as certain mines in the American Southwest or China [1]. The specific gravity of turquoise generally ranges between 2.60 and 2.85, which can sometimes be used as a preliminary test to differentiate natural stone from certain synthetic imitations. Because turquoise is opaque and forms in nodules or veins within host rock, it is rarely found as large, perfect crystals, making massive, high-quality pieces exceedingly rare.

Understanding the Matrix

A key feature many collectors seek is the matrix—the remnant host rock material that surrounds the turquoise veins. The interaction between the blue mineral and the surrounding rock creates patterns that are as diverse as fingerprints. The matrix itself is often composed of limonite, quartz, chert, or sandstone, depending on the geological setting. • Spiderweb Matrix: Highly prized are stones exhibiting fine, delicate lines or webbing across the surface. This pattern occurs when the turquoise material fills minute fractures radiating outward from a central point in the host rock [1]. *Image Placeholder: ◦ InsertImageofHigh−QualityTurquoisewithSpiderwebMatrixHere−Refere InsertImageofHigh −QualityTurquoisewithSpiderwebMatrixHere − * • Webbing vs. Blotchiness: A desirable spiderweb matrix has fine, interconnected lines that follow a natural, organic flow. The matrix itself can range in color from black (often limonite or manganese oxides) to brown or reddish hues (due to iron oxides) [1]. A desirable matrix should contrast sharply with the body color of the stone, enhancing the overall visual appeal. Conversely, large, blotchy areas of matrix that obscure the blue or green are generally less desirable.

Grading and Valuation

1. The value of turquoise is determined by four main factors, often referred to as the “Four C’s” of Turquoise, adapted for this unique gemstone [1]: Color: Pure, rich sky-blue commands the highest price, especially stones matching the historic Persian turquoise standard. Deep, consistent coloration is paramount. The term “Robin’s Egg Blue” remains the benchmark for excellence. 2. 3. 4. Matrix: The presence, style, and color of the matrix pattern are crucial. A f ine, intricate spiderweb pattern generally increases value significantly, provided the blue body color remains dominant and attractive. Stones with no matrix (known as “block” or “pure” turquoise) can also command high prices if the color is flawless. Clarity/Treated vs. Natural: Untreated (natural) stones are far more valuable than stabilized or reconstituted ones. Because turquoise is soft, most commercially available material is stabilized. Provenance showing a stone is “untreated” or “natural” can increase its value exponentially, often by a factor of ten or more [4]. Buyers must be wary of greenwashing terms; a natural stone must retain its original composition. Cut and Carat Weight: The craftsmanship and overall size contribute to the f inal price. Because large, high-quality nodules are rare, larger untreated stones carry a substantial premium. The cut is usually cabochon to maximize color visibility, though fancy cuts are sometimes used. Mohs Hardness and Density: The Mohs hardness scale rating of 5-6 means that handling and wear must be cautious. Specific gravity measurements help identifydensity variations, which can be useful when verifying authenticity against known standards.

Treatment and Stabilization

Due to its relative softness (Mohs hardness of 5–6) and natural porosity, turquoise is susceptible to environmental damage. Consequently, the vast majority of turquoise on the market today has undergone some form of treatment to enhance durability, improve color, or stabilize the stone for setting [1]. Transparency about treatment is ethically paramount in the gemstone trade. • • • • Stabilization (Resin Impregnation): The most common treatment, involving forcing epoxy resin into the porous stone under vacuum pressure to increase hardness, fill fissures, and improve luster. This process significantly reduces its value compared to natural, untreated stone [4]. Stabilized stones are often marked as “stabilized” or “backed.” Dyeing/Color Enhancement: Used to intensify faint blue colors or mask poor quality areas. Dyes can leach out over time, especially when exposed to solvents. Reconstitution: Crushed turquoise powder mixed with a binder (like epoxy) and pressed into a solid block. These pieces lack the unique characteristics of natural matrix formations and are the least valuable form of imitation. Heat Treatment: Occasionally used to change the iron state, theoretically shifting a green stone toward blue, though this is less common and often results in inconsistent color. Identifying Treated vs. Natural Turquoise Authentic dealers will always disclose treatments. If a stone appears too perfect, too uniformly colored, or if it exhibits an unnaturally high polish for a soft material, testing may be warranted. Immersion testing can sometimes reveal a difference in density between natural and stabilized material.

Caring for Your Turquoise Jewelry

Turquoise is a relatively soft and porous stone, making proper care essential to maintain its beauty and prevent its delicate color from shifting or fading [1]. Turquoise is highly reactive to external chemicals and temperature fluctuations. • • • Chemical Avoidance: This is the most critical rule. Keep it strictly away from perfumes, cosmetics, hairspray, chlorine (e.g., swimming pools or hot tubs), household cleaning agents, and excessive heat or direct sunlight, as these can cause color change (often fading to a dull greenish-white) or chemical degradation [1]. The oils on human skin, while generally benign, can slowly affect very soft stones over decades. Cleaning Protocol: The safest method involves wiping gently with a soft, barely damp cloth (distilled water is best), followed by immediate drying with a clean, soft cloth. Never use ultrasonic cleaners, steam cleaners, or abrasive chemical dips. These methods can destroy stabilization resin or permanently damage the natural stone structure [1]. Storage: Store separately in a soft pouch or fabric-lined compartment to prevent scratching from harder gemstones like diamonds or sapphires. Avoid storing it in high-humidity or very dry environments, as rapid changes can stress the stone. When applying lotions or sunscreen, ensure the turquoise jewelry is removed first. Environmental Impact on Color (Patina) Some collectors actively seek the color change that occurs naturally over time, known as patina. A naturally achieved patina, where the color darkens or deepens due to years of natural exposure to skin oils or mild atmospheric changes (not harsh chemicals), is generally viewed positively, especially in older Native American jewelry. However, unwanted chemical fading is irreversible.

References

[1] Turquoise Value, Price, and Jewelry Information. (Accessed via GEMSOCIETY). [2] Guide to Turquoise. (Accessed via TurquoiseJewelry.com). [3] A Guide to Turquoise: Meaning, Properties and Everyday Uses. (Accessed via Hawk House). [4] Choosing the Right Turquoise Gemstone. (Accessed via NaturalGemstones.com).

Conclusion: A Timeless Treasure

Turquoise remains a beloved gemstone, connecting wearers to ancient traditions and the raw, untamed beauty of the natural world. From the pure, deep blues of Nishapur to the intricate spiderweb matrices of the American Southwest, this copper-bearing mineral tells a geological and historical story with every hue and line. Understanding its origins, geological quirks, and proper care is key to appreciating its lasting allure and ensuring this “sky stone” endures for future generations.